Beni Hasan Tomb 3 Khnumhotep II (BH3) is notable for the depiction of caravans of Semitic traders ("Procession of the Aamu").

Is that animal at the far right the Rhim or Slender-Horned Gazelle, Gazella leptoceros? I think of the Canaanite god Resheph: that is His Symbol.

Henry O Thompson, Mekal, the God of Beth-Shan [1970], pp.153-5:

{p.153}

Of particular interest is the Karatepe gate inscription, in which Resheph (Phoenician text) is represented in the Hittite hieroglyphic text

53 JAOS LXXIII, 88. He sees this analogy as the “‘key’”’ to understanding the gazelle’s relationship to Resheph. It is of interest of course, that Egyptian thought related the vulture and “harm” in the light of the Nergal/Resheph relationship just discussed. We can add to this that it formed a determinative in the hieroglyphic word for “terror” (GEG, p. 469, No. G. 14). However, the Egyptian usage varied, for the vulture also means “‘mother.”’ The goddess was Nekhbet, who, combined with the cobra goddess, Edjo, meant, ‘““IT'wo Ladies,” a title for the king (¢bid., No. G. 16). Gardiner also notes that the queen was the incarnation of Edjo, commonly known as Buto, as the pharaoh was the incarnation of Horus, the falcon. The two were hence used as determinatives in hieroglyphic inscriptions (bid., p. 32 n. 1).

54 She wears a feather headdress similar to the one worn by the Philistines. Cf. ANEP, No. 573: 2; RAPLA, pp. 144f, indicates she was a member of a triad at Elephantine.

55 JAOS LXXIII, 88. Cf. the same idea in relation to the hippo, chap. VI, p. 141. BGE II, 283, sees the gazelle as symbolic of Resheph’s sovereignty over the desert. Set of course, was the desert god par excellance. Simpson (p. 88), calls special attention to the “cippi” of Horus in which the young god is shown triumphantly standing on crocodiles, and clenching scorpions, snakes, a lion, and an antelope or a gazelle (e.g., N. E. Scott, “The Metternich Stela,’ BMMA IX [1950-1951], 206, who says, however, that the animal is an orynx). He fails to note that these are all animals of Set, the ancient enemy of Horus. So far as the writer knows, there is no evidence that Resheph was singled out as the enemy of Horus, although as an Asiatic god who could be identified with Set, he would fill this role (cf. chap. VI, n.92.)

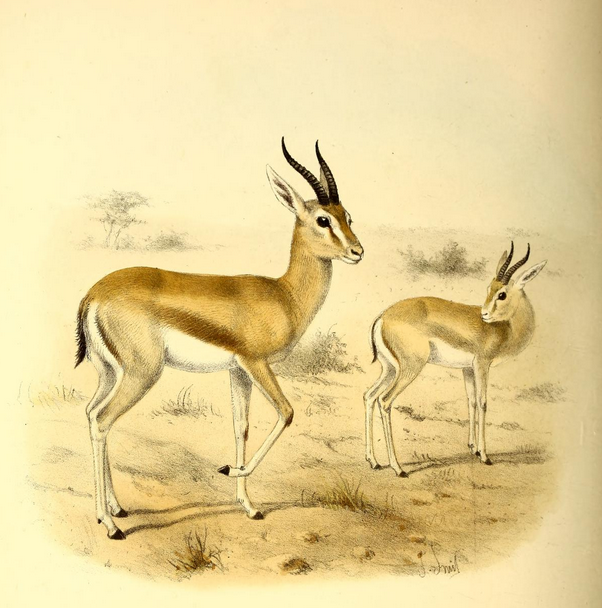

{p.154} by the antlered head of a stag. “It might therefore be suggested that the animal associated with Reshef is a stag in Anatolia and a gazelle in Egypt, where the stag is uncommon.” He feels that the gazelle and antelope leading the procession of ‘Amu in the Beni Hassan tomb, supports this view, for the Egyptians specifically associated these animals with the ‘Amu over a century before the ‘Eper-Resheph text.56

Simpson's whole point is to show that Resheph really was somehow related to the gazelle. Surely the presence of the gazelle head on his forehead is sufficient for this. Its occasional presence elsewhere does not detract from this.57 The argument presented above is a bit obscure also in that it does not explain why the antelope and the goat did not share in the development. Since there apparently is no lack of gazelles in Anatolia (nor Syria), one wonders why there should be a sharp distinction between stags and gazelles in that area. Actually, ancient art did not always make a clear distinction among these animals. This is particularly apparent in glyptic art.58 Simpson goes on the refer to Albright’s identification of the gods of pestilence, Nergal and Resheph, as gazelle gods.59 We should note that Albright is also presenting them as fertility gods, and the gazelle as a fertility emblem. This dichotomy of destruction/fertility is quite appropriate to chthonic deities. The fertility aspect, however, removes the entire foundation of Simpson’s suggestion for the significance of the gazelle as paralleling the Egyptian cobra and vulture. If the gazelle did bear this analogy in Egypt, there would of course be no guarantee that it would have such a significance in Asia.

Other Relationships.

The gazelle, as already indicated, was not restricted to Resheph.60 Prominent among these associations with the gazelle and/or related animals, was the Great Mother, or fertility goddess.61 We would include here the “‘potnia théron” with her goats, {p.155} from Ras Shamra.62 One of the more interesting examples of a gazelle goddess is the wild huntress from Lebanon, known at an early date in Egypt. She is probably the nude woman astride a horse illustrated on a potsherd from XIXth Dynasty Thebes. Her name, “Asiti” or “‘Asith,” may be a feminine form of Esau. 63

The last has been identified with a Phoenician deity, ‘“Usous,” “Ousoos” or the like, as well as the more usual, “Edom,” either as a deity, or the progenitor of the country.64 He was connected with the thunderbolt, and he and his twin brother (in Phoenicia) were mighty sons of Light, Fire, and Flame. In addition, he was a hunter. This leads rather naturally to the biblical Esau. While the gazelle was not used as a sacrificial animal by the Hebrews, it is not impossible that a sacrificial meal may be the background for the blessing of Isaac story.65 We should note that the gazelle and related animals were used on occasion for sacrifice by other peoples.66

...