Peter Kirby wrote: ↑Sun Feb 18, 2024 10:57 pm I have added two links to papers on the "Christianos Graffito" found at Pompeii (buried in 79 CE) in the 19th century. The discussion of the inscription has always been marred by association with far-fetched speculation that goes well beyond the evidence. It also took a firm step backwards early on by the publication of the inscription in the well-known reference, Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum vol. 4, in a greatly obfuscated form (but without any new evidence to justify the many changes made, relative to the three eyewitness accounts).

A turning point in the discussion came from M. Guarducci, “La più antica iscrizione del nome dei Cristiani”, in: Romische Quartalschrift, 57 (1962), pp. 116-125. Guarducci identified the probable first word of the inscription, the name "Bovios." This led to the reconstruction of this line of the inscription as "Bovios is listening to the Christians." Like others, Guarducci also identified the fourth and fifth lines as coming from a different hand.

Guarducci, Wayment and Grey, and Tuccinardi differ in their reconstruction of the fifth line.

Jesus Followers in Pompeii: The Christianos Graffito and “Hotel of the Christians” Reconsidered

https://www.jjmjs.org/uploads/1/1/9/0/1 ... ompeii.pdf

Christian Horrors in Pompeii: A New Proposal for the Christianos Graffito

https://www.jjmjs.org/uploads/1/1/9/0/1 ... inardi.pdf

For the purpose of this thread, the most interesting part of the inscription would be the presence of the word Christianos (accusative plural).

There are three accounts here: Giuseppe Fiorelli (the archaeologist who found the inscription first), Giulio Minervini (another archaeologist who arrived soon after in order to make a sketch), and Alfred Kiessling (an archaeologist who saw it later that year, making another sketch).

The statement from Fiorelli was that he “read at the end of the first line . . . HRISTIANOS or . . . HRISTIANVS.” Fiorelli indicates, by this, that he was not able to make out clearly the letter before 'H' here. The statement from Fiorelli can be compared to the two sketches regarding this part of the inscription (the fourth and fifth lines):

All three witnesses are very clear about the letters 'RISTIAN' here. The first two witnesses clearly saw the end of the word here (which Fiorelli says was "OS" or "VS" and which Minervini sketched as "OS"). The first two witnesses also saw the "H" here as well, which Kiessling's sketch can show only in a deteriorated form. Of course, Kiessling was aware that the graffito was already on its way to fading, which is the best explanation of why the "H" is not clearly visible in Kiessling's sketch and why the last two letters now left only one line visible to Kiessling.

As a result, we can conclude that the graffito read 'HRISTIANOS' here. The first letter must have been hard to make out, based on Fiorelli's statement. Both Minervini and Kiessling attempt to draw the preceding letter: Minervini more clearly as a 'C', Kiessling as just a slightly curved line. All three witnesses may have been dealing with damage at this part of the graffito already.

Even with the difficulty of reading the first letter (which might be marked as a letter whose form is being reconstructed from context), a fairly cautious conclusion regarding the the inscription having the word 'Christianos' here can be reached.

Being cautious

https://www.phrasebank.manchester.ac.uk ... -language/

One of the most noticeable stylistic aspects of academic communication is the tendency for writers to avoid expressing absolute certainty, where there may be a small degree of uncertainty, and to avoid making over-generalisations, where a small number of exceptions might exist. This means that there are many instances where the epistemological strength (strength of knowledge) of a statement or claim is mitigated (weakened) in some way. In the field of linguistics, devices for lessening the strength of a statement or claim are known as hedging devices. Analysis of research reports have shown that discussion sections tend to be particularly rich in hedging devices, particularly where writers are offering explanations for findings.

Being critical

https://www.phrasebank.manchester.ac.uk/being-critical/

As an academic writer, you are expected to be critical of the sources that you use. This essentially means questioning what you read and not necessarily agreeing with it just because the information has been published. Being critical can also mean looking for reasons why we should not just accept something as being correct or true. This can require you to identify problems with a writer’s arguments or methods, or perhaps to refer to other people’s criticisms of these. Constructive criticism goes beyond this by suggesting ways in which a piece of research or writing could be improved.

… being against is not enough. We also need to develop habits of constructive thinking.

Edward de Bono

Two criticisms are cited between the two papers cited above (which I have read):

(1) “a figment of pious imagination”

The first is from the classical historian Mary Beard in "The Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found" (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 302. Here the criticism is described as 'dismissing a Christian reading of the graffito as “a figment of pious imagination,” although typically without carefully engaging the full range of relevant evidence.' Elsewhere the author is described as "open to the possibility that Christians were in the city of Pompeii, but do not include the Christianos graffito as evidence". It might be added that Mary Beard has produced historical documentaries which include the martyrdom of Perpetua.

(2) 'accusations of fraud - the original eyewitnesses invented

the graffito and that “in fact, probably no one ever saw it!”

This second criticism is from the author Eric Moorman from his article "JEWS AND CHRISTIANS AT POMPEII IN FICTION AND FACTION." The author discusses the Christian inscription as follows:

The christianos inscription

One of the most frequently studied graffiti is that of christianos, a word that originally formed part of a longer text that faded shortly after its discovery in 1862, as it had been written with charcoal. Alfred Kiessling had apparently noticed it on the south western wall of the atrium of a house in the Vicolo del Balcone Pensile (VII 11, 11) in 1862. The story of the discovery and the documentation by Kari Zangemeister (CJL IV 679) and others contains a great deal of suppositions that make it rather suspect. In fact, probably no one ever saw it!

Moreover, the two transcriptions of the text show great differences, including the spelling of the word itself/ and it has been suggested that the word never actually existed. Giuseppe Fiorelli, who made a (third), unfortunately unpublished copy of the text, wanted to interpret christianos as the name of a wine. Margareta Guarducci, one of the leading experts in the field of ancient epigraphy, renowned within and beyond Catholic and scientific circles alike for her research on the tomb of S. Peter beneath the papal altar in S. Peter's cathedral, strives to read some Christian content into the texts and constructed the sentence as follows:

Bovios audi(t) christianos/s(a)evos o[s]ores

///

'Bovius listens to the Christians, those cruel haters/

albeit without explaining her reasoning.

https://www.researchgate.net/publicatio ... nd_Faction

Prior to this section Eric Moorman also identifies three earlier fiction books the subject of which involved the community of Christians in Pompeii. These books were in circulation prior to the discovery in 1862. He discusses these three books in depth and then writes in his summary:

Fiction versus Faction

Upon examining the precise timing of discovery of these possible (or imagined) proofs of the presence of Jews and Christians at Pompeii, we can conclude that none of them were known when our three discussed authors (Bulwer, Anonymous, and Fairfield) wrote their

texts.

https://www.researchgate.net/publicatio ... nd_Faction

To the above I can add my own criticism in the form of a sketch of a brief timeline:

1853 - Pius IX moved beyond collecting [Christian relics] by appointing a commission - "Commissione de archaelogia sacra" - that would be responsible for all early Christian remains."

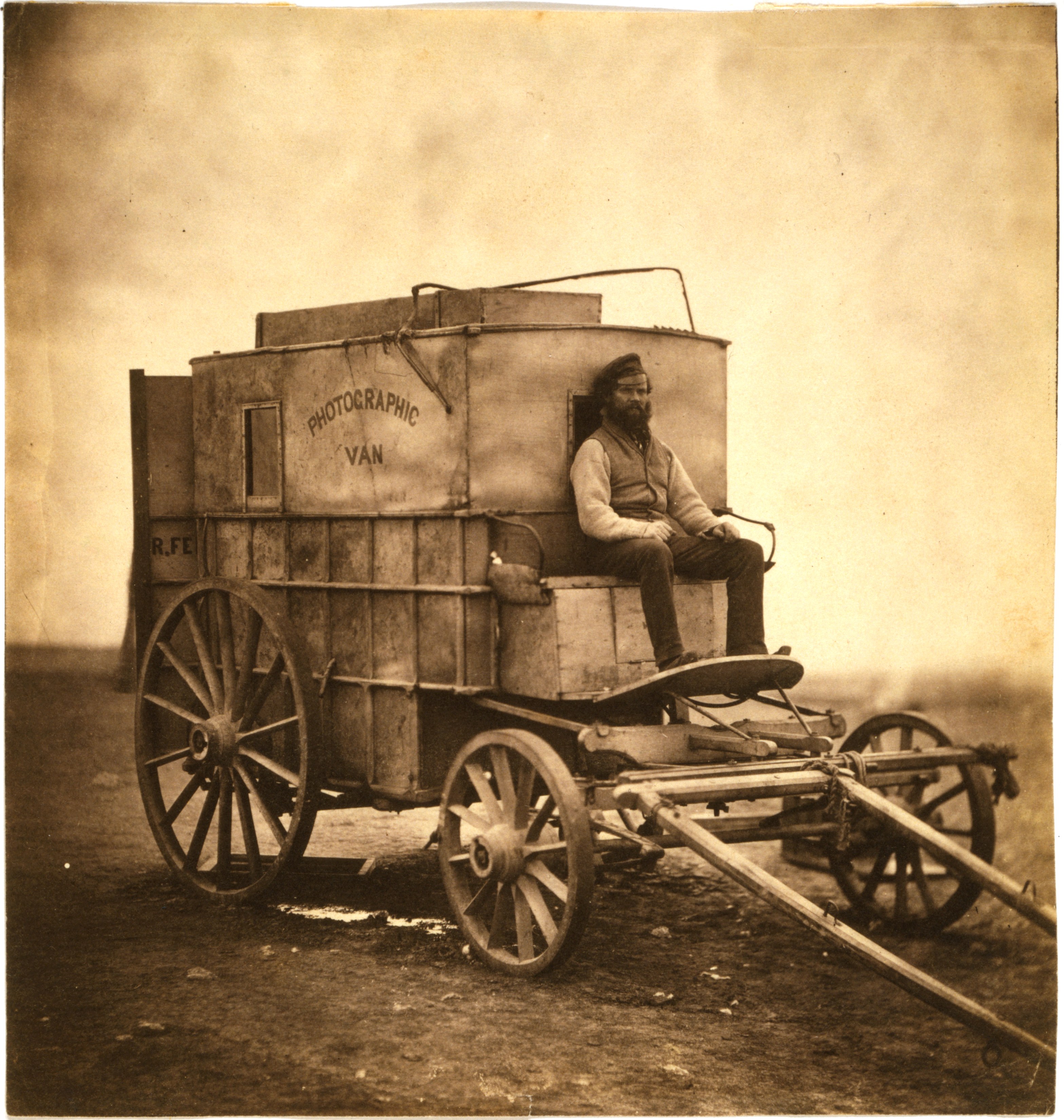

1855 - Roger Fenton's assistant seated on Fenton's photographic van, Crimea

1857-1861 Giovanni Battista de Rossi publishes first volume of "Inscriptiones christianae urbis Romae". The first volume had to be revised due to (multiple) identified frauds.

1862 - Pompeii graffito is discovered by the eminent Neapolitan archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli

1862 - Neapolitan archaeologist, Giulio Minervini, “sketched the signs appearing on the wall.”

1862 - German archaeologist Alfred Kiessling, who was the last scholar to see the artifact in person and the first to publish the related news (Bullettino of 1862 with transcription of the two lines) that “. . . a charcoal inscription was found, unfortunately largely vanished. . . . As far as I know, this is the first of the monuments found in Pompeii, referring to the Christians”

1864 - Visit by Fiorelli and Giovanni Battista de Rossi, but by then the charcoal graffito had completely disappeared.

1871 - Karl Zangemeister authored the official edition of the graffito [7] for the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL IV.679), also publishing Kiessling’s apograph (Tab. XVI.2) for the first time. Kiessling’s apograph, was the later testimony. He changed the Christianos into ceristirae or christirae

1900 --------------------------

1961 - Margherita Guarducci “Bovio is listening to the Christians, cruel haters.”

2005 - ERIC M. MOORMANN "Jews and Christians at Pompeii in Fiction and Faction". Included accusations of fraud - the original eyewitnesses invented the graffito and that “in fact, probably no one ever saw it!”

2014 - Mary Beard, Fires of Vesuvius, 302; cf. Alison E. Cooley and M. G. Cooley, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook (2nd ed.; London: Routledge, 2014), 107–108, 159 ( “a figment of pious imagination” )

2015 - Thomas A. Wayment "Jesus Followers in Pompeii: The Christianos Graffito and “Hotel of the Christians” Reconsidered. JJMJS No. 2 (2015): 102--146

2016 - Enrico Tuccinardi "A New Proposal for the Christianos Graffito"; JJMJS No. 3 (2016): 61--71

Four Points:

1) If a photograph of the inscription was captured before it disappeared I would be less skeptical.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_photography

2) The involvement of the papal archeologist Giovanni Battista de Rossi, even at arm's length, rings all sorts of warning bells for me.

3) The involvement of Pope Pius IX who "moved beyond collecting [Christian relics] by appointing a commission - "Commissione de archaelogia sacra" - that would be responsible for all early Christian remains" also rings all sorts of warning bells.

4) All other epigraphic and physical manuscript evidence related to the nation of the Christians appears in the 3rd century with nothing from the first two centuries other than this "discovery" from the 1st century which within days disappeared under the Pompeii rainstorms.

Conclusion

My fairly cautious conclusion (FWIW) is that this supposed 1st century Pompeii graffito has very little historical integrity.